Why Is the U.S. Dollar Declining?

T.S. Eliot wrote that "April is the cruelest month." For the U.S. dollar, that certainly seems to have been the case this year. As of April 24th it had fallen by 4.9% since the start of the month, when the U.S. announced a wide array of tariffs on trading partners. It was one of the largest monthly declines since 2009. It is currently down 7.3% from its 2025 peak on January 13th.

The dollar's drop has raised concerns because it coincided with a spike in U.S. interest rates—an unusual event. Typically, when U.S. bond yields are higher than those in other major developed countries, the dollar rises. During times of heightened market volatility, Treasury yields tend to fall, because historically U.S. Treasuries have been perceived as a "safe haven" amid uncertainty. However, in early April the pattern reversed.

The dollar dropped recently despite U.S. bond yields moving higher vs. yields in other major markets

Bloomberg. Daily data from 4/23/2020 to 4/25/2025.

The Bloomberg US Aggregate Index (LBUSTRUU Index) is a broad-based gauge of the performance of the investment-grade, U.S. dollar-denominated, fixed-rate bond market. The Bloomberg Global Aggregate ex-USD Index (LG38TRUU Index) is an investment grade, multi-currency benchmark including treasury, government-related, corporate and securitized fixed-rate bonds from both developed- and emerging-market issuers. The Bloomberg US Dollar Spot Index (BBDXY Index) tracks the performance of a basket of global currencies against the U.S. dollar. Indexes are unmanaged, do not incur management fees, costs and expenses and cannot be invested in directly. Past performance is no guarantee of future results.

The most likely explanation is that investors sold dollars because they were reacting to the widespread imposition of tariffs that they believed could slow U.S. growth and reduce the expected return on investment. The tariff announcements caused investors to reassess the outlook for the economy. In addition, President Donald Trump's comments about potentially replacing Federal Reserve Chair Jay Powell due to differences over interest rate policy likely caused investors to pull back. The independence of the central bank is important to investors. Consequently, risk aversion rose and because the U.S. appeared to be the source of the risk, investors likely moved out of dollar-denominated assets.

More volatility likely ahead

If the U.S. continues to pursue an aggressive trade policy, the dollar is likely to trend lower. Tariffs are expected to cause gross domestic product (GDP) growth and corporate earnings to slow. Recent data suggest the economy is already slowing due to tariff issues. The Federal Reserve's latest Beige Book survey, released on April 24th, cited the word "tariffs" 107 times as a concern for its regional banks. It indicated that only five of the regional banks saw an increase in activity, three said activity was unchanged and four pointed to slowing activity.

Given the prospects for slower growth, investors may be starting to look elsewhere for higher returns. That's a problem for the U.S., because we run a large fiscal deficit that needs to be financed with foreign capital. The high level of uncertainty and continued volatility in policy could discourage capital inflows.

Foreign investors are beginning to shift allocations

It appears that investors have begun to reduce allocations to U.S. markets after years of accumulating U.S. dollar assets. Measuring inflows and outflows in assets globally is difficult to track. When it comes to official holdings by foreign central banks, we get data from the Fed but it's reported with a two-month lag. As of the end of February, the numbers didn't show that foreign central banks or households had reduced their holdings of U.S. Treasuries significantly.

However, Japan's Ministry of Finance recently reported1 that domestic investors were net sellers of foreign bonds for six consecutive weeks from early March to mid-April, suggesting that a shift to reallocate assets to other markets may have begun.

Over the long run, foreign central bank holdings tend to be relatively stable while private sector investments are more volatile. It is likely that foreign households, which increased their investments in the U.S. over the past few years, have begun to repatriate capital. With the U.S. tech sector coming under pressure this year and prospects for growth in Europe and Japan picking up, investors looking for better returns appear to have migrated into those markets.

Foreign private Treasury holdings have outpaced foreign government Treasury holdings

Source: Bloomberg and the Schwab Center for Financial Research, using monthly data from 2/28/2010 to 2/28/2025.

"Foreign Official" holdings are represented by the U.S. Treasury Securities Foreign Holders Foreign Official (HOLDTFO Index). "Foreign Private" holdings are represented as the difference between US Treasury Securities Foreign Holders Foreign Official (HOLDTFO Index) and US Treasury Major Foreign Holders Total (HOLDTOT Index).

However, it's important to note that the dollar rose sharply for more than a decade from 2011 until its peak in 2022, increasing by about 50%. Since the peak it has held at a relatively high level as U.S. economic performance outpaced that of most other countries, drawing in investment capital. Even after its recent drop, the dollar is still more than 40% above where it was a decade ago against a basket of currencies. There is scope for a cyclical decline from these levels without signaling a crisis, because foreign investors have accumulated so much in the way of dollar assets.

Even after its recent drop, the dollar is still well above its 2011 level

Source: Bloomberg. Daily data from 4/1/2011 to 4/25/2025.

The Bloomberg US Dollar Spot Index (BBDXY Index) tracks the performance of a basket of global currencies against the U.S. dollar. Indexes are unmanaged, do not incur management fees, costs and expenses and cannot be invested in directly. Past performance is no guarantee of future results.

However, there is no obvious replacement for the dollar as a reserve currency. The U.S. has the largest and most liquid bond market in the world. Most global financial transactions are conducted in U.S. dollars, creating underlying demand for central banks to hold them. In addition, the dollar is supported by strong legal structures and an independent central bank. Those characteristics are not matched by many other currencies.

What could a weaker dollar mean for the bond market?

A weaker dollar means that U.S. interest rates may not fall as much in this cycle as would otherwise be the case. We do see scope for the Fed to cut rates later this year. But foreign investors may not be as willing to fund U.S. deficits as readily as in the past, limiting the decline in yields. Moreover, if efforts to reduce the trade deficit are successful, then capital inflows will diminish anyway. In the balance of trade, a deficit in goods and services is offset by a surplus of capital.

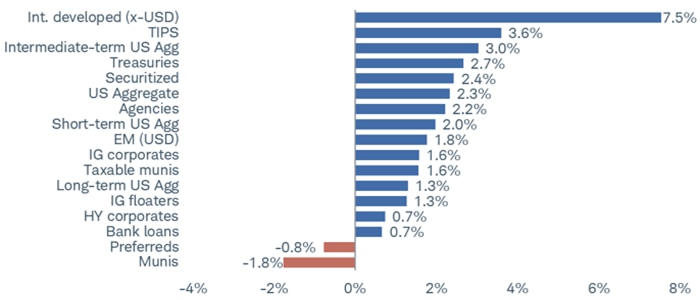

From an investment point of view, diversifying internationally looks like it makes sense in this environment. Although bond yields in most developed countries are lower than in the U.S., the gain in foreign currency returns can offset the yield gap. International diversification may also help mitigate volatility. Year to date, international bonds have had the highest returns of the fixed income asset classes.

Year-to-date returns for various fixed income investments

Source: Bloomberg. Total returns from 12/31/2024 through 4/24/2025.

Total returns assume reinvestment of interest and capital gains. Indexes are unmanaged, do not incur management fees, costs and expenses and cannot be invested in directly. For more information on indexes, please see schwab.com/indexdefinitions. Indexes representing the investment types are: Preferreds = ICE BofA Fixed Rate Preferred Securities Index; HY Corporates = Bloomberg US High Yield Very Liquid (VLI) Index; Bank Loans = Morningstar LSTA US Leveraged Loan 100 Index; Long-term US Agg = Bloomberg U.S. Aggregate 10+ Years Bond Index; IG Floaters = Bloomberg US Floating Rate Note Index; IG Corporates = Bloomberg U.S. Corporate Bond Index; US Aggregate = Bloomberg U.S. Aggregate Index; Intermediate-term US Agg = Bloomberg U.S. Aggregate 5-7 Years Bond Index; Municipals = Bloomberg US Municipal Bond Index; Treasuries = Bloomberg U.S. Treasury Index; EM (USD) = Bloomberg Emerging Markets USD Aggregate Bond Index; Securitized = Bloomberg US Securitized Bond Total Return Index; Agencies = Bloomberg U.S. Agency Index; TIPS = Bloomberg US Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities (TIPS) Index; Short-term US Agg = Bloomberg U.S. Aggregate 1-3 Years Bond Index; Int. developed (x-USD) = Bloomberg Global Aggregate ex-USD Bond Index. Past performance is no guarantee of future results.

Overall, the dollar looks likely to weaken over the course of the year, barring any major surprises in policy. However, we don't see it losing its status as the world's reserve currency. For the U.S. Treasury market, yields are likely to fall later in the year with Fed rate cuts, but the risk premium for holding longer-term bonds versus short-term bonds will likely remain elevated. We continue to favor holding high-credit-quality, intermediate-term bonds in this environment.

1 "Japanese investors turned net buyers of overseas bonds last week," Reuters, April 24, 2025.